Physical Address

Most of the time though, a decent course syllabus will give students a couple of options.

How to Memorize a Textbook (3 Techniques)

Memorizing a textbook, although it’s a heavy process, can sometimes be the only way to make sure you pass a particular class.

But what’s the best way to go about it?

Here’s the short answer on how to best memorize a textbook:

First, pick the right book. Then give yourself time (a week per one hundred pages). Finally, break the book down into “chunks”, “hooks” and mnemonics that can help you memorize and recall its material in sequence.

If that sounds like a difficult task, that’s because it is. You’ll need to be patient and committed to making it work.

We’ll get into how best you can do that in this article.

Here’s what else we’ll cover:

- Memorization techniques you can apply to textbooks

- General tips

- My own personal strategy

As a med student, that last point could prove interesting. But I’m confident it could also help students across any subject or discipline!

Ready to get started? Let’s go!

How To Memorize A Textbook Effectively

Let’s focus on the first steps of the approach; choosing which book to memorize.

Book Selection

You’re not always free to choose which book to memorize. Depending on your professor or class, there’s often only one option.

If you’re in that situation, for the sake of your grade, I urge you not to change!

Most of the time though, a decent course syllabus will give students a couple of options.

So this is where your first major part of research comes in; drilling down on which book is best to memorize.

Here’s what I feel is best to think about:

- Reputation (is the book well-reviewed by other students of the same course?)

- Length (the shorter the better!)

- Style (image-heavy, simple explanations etc.)

Keep a list of the titles you feel best match these criteria (I do something similar on my recommendations page). Note down the total number of pages as well as any of the major pros and cons you come across.

Think about which book you could see yourself putting the most effort into memorizing.

Image-based books are great because they tend to convey ideas and concepts in a more memorable way.

While review-style books, especially as they’re shorter and deliver the most relevant facts and information, can be useful too.

Either way, these are the types of books that will be much easier to memorize compared to gigantic textbooks.

Seek to Understand

This part sounds counterintuitive, but it works.

Look at this project as a goal to understand rather than memorize.

Framing it this way makes the whole process easier.

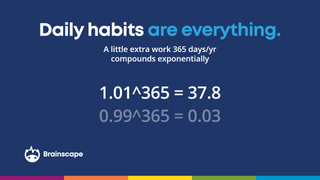

Learning compounds. Concepts build on top of one another. Understanding reduces time spent re-memorizing.

Spend the initial effort to contextualize the information first.

The Reading Process

Before diving into specific techniques, it’s probably worth spending time figuring out what makes a good book to memorize.

Take your list from above and run through the following process:

- Skim each books contents; look at chapter headings, summary sections etc

- Look at images and diagrams

- Look for sample questions to help quiz you on key concepts

- Evaluate the style; is it easy to understand?

- Think about how much of the book you need to memorize; the whole thing or just a small part?

Compare each and pick the one that seems best suited to your own personal tastes and preferences.

And don’t worry if it’s not on your teacher or departments’ “recommended list”.

Active Reading

It’s important you don’t passively read when attempting to memorize. You’ll make faster progress dividing up your time and recalling what you’ve read aloud or on paper.

Drawing mind-maps can help you associate parts of what you’ve read too. As well as helping you interlink the concepts. You can use things like whiteboards or tablets to help with this.

Spacing

Once you have chunked your reading sessions and summarised the core aspects it’s important you find a way of archiving this information.

If you prefer the old-school method of pen and notebook try and index your question prompts taken from your reading and space out how often you plan on reviewing them.

Memorization takes time. That’s why a general rule of thumb is to revisit what you’ve learned and actively recall it, in intervals. A good system is a day, weekly, fortnightly, monthly system. But do whatever feels best.

Consolidation

The final approach is to apply what you’ve learned. This means answering questions. And lots of them.

Thankfully good textbooks will have example questions, testing the material you read, included inside. Otherwise, you can practice with topic-based resources you can find all over the web.

The important thing is you practice, get things wrong, and understand why you got things wrong. Thus helping you understand a book. And, as a consequence, better memorize it.

How to Memorize A Textbook: Effective Memorization Techniques

Here’s where I’ll get more into the weeds as to what you should do next once you’ve settled on your book.

The following techniques could help.

Dominic System

Invented by eight-time World Memory Champion Dominic O’Brien, the Dominic system is a great method to remember strings of digits (values, rates, etc).

Simply put, it’s a naming system designed to play on personal relationships. Substituting numbers for initials, you can then better recall the sequence.

To better explain this, imagine we’re studying from a hematology (blood) book and we need to memorize the lab range values for partial thromboplastin time (PTT). In the book, it tells us the correct values are between 60-70 seconds in the human body.

Applying the Dominic method to remember this could work the following way:

- First encode all the numbers with letters; A(0)B(1)C(2)D(3)E(4)F(5)G(6)E(7) etc

- Code 60, using the system, to GA; Giorgio Armani (random – but you can use sites like peoplebyinitials.com to find famous people with initials, or use people known to you)

- Code 70 the same way to EA; Emmanuel Adebayor (soccer player – yes, I’m a fan)

- Then come up with an image of Adebayor playing football/soccer in a bloodied (for the thrombin value) Armani suit (remembering the values 70-60)

Weird but it works.

And even more powerful when used with the Method of Loci technique (more on this later).

Pegword Method

This method is quite similar to the Dominic method except it uses a rhyming scheme. It’s used by a lot of memory champions to recall lists of things too.

Using medical students as an example again; this could be useful to recall common symptoms of certain pathologies. Specifically, those listed out in UFAPS (top med school review books).

It works by recalling each item on a list as a “peg”. With each “peg” matching with an object that rhymes with the number.

| One | Gun |

| Two | Shoe |

| Three | Tree |

| Four | Door |

You then associate your list of things with those “pegs”.

Take for example (sticking on the subject of pathology), the three main symptoms of aortic stenosis; angina, syncope, and dyspnea. Not exactly hard to remember “ASD” as a mnemonic, but using the pegging system you could recognize them more clearly:

- Angina you recall as a compressed gunshot

- Syncope as someone passed out missing one shoe

- Dyspnea as someone out of breath hunched under a tree

This again uses images to aid memorization. You’ll remember there are exactly three of them. And what each of them is.

Method of Loci

Both the previous memory techniques lean heavily on this one. You might have heard it sometimes referred to as the “memory journey” or “memory palace.” It’s also mentioned in the TV shows Hannibal and Sherlock.

Originally born out of Ancient Greece and Rome, this technique went under some resurgence in popular culture during the 60’s thanks to the book The Art of Memory.

Nowadays, it’s pretty well documented, combined with some others, as the primary go-to technique of people seeking to memorize large amounts of information.

It works by memorizing a location; university, a shop, your home, etc, and “fixing” items (the information you want to recall) to places in that location. Then walking through that location in your mind and recalling each thing in sequence.

The idea is the subject uses these places to build an association between distinct pieces of information.

Applying this to memorizing a textbook could involve breaking down a chapter into an individual location. Then doing something like the following:

- Have subheadings of a chapter correspond to a point in the location; with an image detailing simply what it’s about

- Fix each point in the order you would move through the location

- Try to make each point interact with another in the same way that the information builds and relates to each other in a book

Interestingly, this technique was also applied in a 2013 psychological study to treat depression sufferers, using their walk through their own “palace” as a way to reaffirm positive thinking.

A very tried and tested approach!

My Personal Strategy: Medical Textbook Memorization

As a medical student sometimes I find these techniques a bit too time-consuming for chunking individual parts of a textbook I have to learn.

The reason I don’t have to lean on them too heavily though comes from the fact that the best medical textbooks do this for you.

Then there’s also the reason of Anki.

Anyone that knows me personally knows how much I love Anki as an app for memorizing basically anything. In medical school, if you didn’t know already, there are whole communities (hundreds of thousands of students) dedicated to using this application too.

That’s how powerful it is!

Anki, for those of you who don’t know, is a digital flashcard system that you can run and synchronize across any device. Meaning you can go through “decks” at home, on the bus, on the run; anywhere you like.

It’s also useful in the fact it’s free. And that a lot of ready-made decks exist out there that save you time having to make your own cards from scratch.

I highly recommend you search out flashcard decks for textbooks you hope to memorize. If they’re popular, chances are there’s a deck available.

How Can I Enjoy Reading Medical Textbooks?

One last thing worth talking about in this discussion is how to enjoy the process of reading. What works for me, might not necessarily work for you.

There are however a few suggestions I think could prove useful – and no, I don’t just mean choose a great book first!

Here are more ideas:

- Pomodoro technique: rewarding yourself after 25 minutes of focused, scheduled reading is one way to make it seem less laborious

- Set reading challenges: maybe with friends, colleagues etc. to see how much of a book you can effectively absorb in a certain amount of time

- Read somewhere other than your usual location: did I mention I love coffee shops for this reason?

Obviously, the key thing here is not to read for the sake of reading. But rather to apply active recall learning techniques to the session. Pausing to ask questions, summarising what you’ve read aloud or using the Feynman technique, etc.

All the things I’ve already detailed.

Oh and note-taking too. Make sure you learn how to take notes effectively. Don’t just blindly highlight or re-copy things either.

Recommended Resources

If you’re interested more in the techniques outlined in this article, the following resources might prove useful.

Udemy’s Memory Courses Online – great selection of courses here although I’ve not done any personally

Magnetic Memory Method – where I originally learned about some of the techniques described in this post

Barbara Oakley’s Mind for Numbers – which explains more broadly the use of such effective memory techniques in the maths and sciences

Summary

Memorizing textbooks should be done with care and attention. Firstly, you should ask yourself if memorizing a book necessary at all? Then, if the answers, yes, maybe consider the following:

- Book selection – choose only the most appropriate/relevant resource

- Apply active learning strategies to your reading – flashcards, memory tricks etc

- Improve your retention with spacing/intervals

- Test yourself with questions to hard-wire what you’re learning

Memorizing is a big part of passing certain courses. Make sure you know how to do it right!

How to read a textbook—and remember what you’ve read

Save yourself hours of study time: learn to read a textbook properly and actually remember what you learn. This guide will teach you how.

When you were maybe five years old, you learned to read. ‘A’ is for apple, ‘B’ is for ball, ‘C’ is for cardioencephalomyopathy, and so on. You were probably fluent in reading by ten or fifteen, and that was that. Reading accomplished.

There’s more to reading than just understanding the words on the page. At Brainscape, we’re experts at studying effectively. Our study experts differentiate between passive reading (or, as many people in these social media times do, skimming) and active reading.

Active reading is a different animal altogether.

Active reading is what you want to do when you’re learning new concepts. It’s what you do when you want to remember what you’ve learned. This especially true when you’re reading a textbook.

Knowing how to read a textbook properly is one of the most important ways to study effectively with less effort.

In this guide, you’ll learn how to read a textbook so that you retain and integrate what you’ve learned. The steps we go through will make the reading process a little longer at first but will save you hours and hours of study time later on because what you’ve read will have been stored in your long-term memory.

Passive reading (aka skim reading) vs. active reading

These days, most people skim read. It’s not entirely our fault. We’ve been conditioned by the endless scroll of social media channels and news feeds. The TL;DR (Too Long; Didn’t Read) approach may be fine when dealing with your aunt’s five-page email about her holiday in Ogallala, Nebraska, but it’s doing you a serious disservice when it comes to reading your textbook to prepare for a vital test.

Normal reading is using your brain like a car coasting in neutral, while you skim through a chapter. Active reading puts your brain in gear, so you’re actually putting data into your memory banks as you read.

The key to active reading is putting your brain into a question-answering, problem-solving gear. And if you prime it with questions before you start reading, it will attempt to answer them.

Here’s how you can do that.

How to read a textbook using active reading

Tip 1. Prime your brain for learning

Before you start reading, spend a few minutes with the ‘what you will learn in this chapter’ section. Just sit with it, and think about it as if you’re about to take a test straight after finishing the chapter.

This puts your mind in a different mode, one where it’ll be actively looking out for the facts, concepts, and information you’ve brought to its attention. In this mode where we’re thinking about and predicting what to expect, we learn better.

Our brains are efficient. They’re bombarded with information all the time, and they discard 99% of it as unimportant.

It’s like the safety briefing before a plane flight. Everyone switches off their brain as soon as it starts because it doesn’t seem relevant. But supposing the pilot began it with: “You know, I have a strange feeling about this flight. One of the engines has been making funny noises, and three black cats crossed my path on the way here …” Everyone would listen a lot more closely to where the exits were and how their life jacket inflates.

Briefing your brain on what to look out for before you start means you’ll be more sharply focussed, and retain information better.

If there’s no ‘what you will learn’ at the start of the chapter, either do a quick skim read to pick up the important points, then think about them for a minute or two, or read the chapter summary at the end.

Tip 2. Imagine how the information might show up in the exam

If you’re reading your textbook because you have a test later, try to predict what the exam questions will be. This prompts your brain into interpreting the material as important, and that it, therefore, needs to concentrate and commit it to memory.

Context is everything. It explains why you’re reading a 37-page chapter on quantum mechanics. And that context is the examination at the end of the term, semester, or year. If that isn’t motivating enough, you may need to remind yourself of your larger career goals. Connecting what you read to something very important in your life will help you stay focused.

Tip 3. Use your hands

There’s quite a bit of research showing that writing notes by hand helps memory retention. It’s not exactly the same, but using your hand to underline or highlight important points does help commit them to memory.

You’re switching your brain into more active engagement when you do this, and the highlighting will help later when you’re studying for an exam.

Tip 4. Become the teacher and teach yourself

At the end of each chapter, before triumphantly slamming your book shut, pause. It’s time to give yourself a lecture on what you’ve just learned. Out loud, deliver a summary of the chapter to yourself, a friend, flatmate, lover, or pet.

Because teaching out loud is one of the most effective ways to solidify new knowledge. This is called the Feynman Technique, after the Nobel award-winning physicist who came up with it: Richard Feynman.

Imagine you’re teaching this chapter to someone who’s never studied this subject before. Outline the key points, the central concepts, and how they relate. Be thorough and don’t assume any baseline knowledge of the subject.

You’re doing four things here:

- You’re reviewing what you’ve learned again, which more deeply engraves the new memories you’ve just created.

- You’re putting this new knowledge into your own words, thus making additional connections your brain can use for retrieval later.

- You’re using a different mode to consolidate the information: verbal, rather than visual.

- Finally, you’re employing free recall .

Free recall means you’re retrieving information from your memory without any cues. (Cued recall would be answering multiple-choice questions, and it’s a much less effective way to learn.) When you have to deliver a mini-lecture, as you talk, your brain is busy hunting out the relevant information and stringing it together in logical, cogent threads.

This really strengthens connections for your memory to use later.

Tip 5. Take study breaks when you need to

If you zone out, take a study break! It’s quality, not quantity that’s important here. Your brain is like a muscle that gets tired from use and if you don’t give it a rest, you’ll waste time trying (and failing) to onboard new information. Having said this, there are things you CAN do to build your attention span so that you’ll be able to concentrate for longer.

Tip 6. Read ahead of lectures

Now you know how to read a textbook properly, let’s look at the best time to read.

Reading a relevant chapter before a lecture sounds like a lot of extra work but it actually saves you study time later on, not to mention a nasty case of carpal tunnel from desperately trying to take down study notes in class. Reading beforehand actually primes your brain for learning and allows you to walk into class armed with:

- An overview of what to expect,

- A preliminary understanding of the material,

- And the areas in which you’re a little uncertain.

Your lectures will carry so much more weight and learning potential if you structure your studies this way, rather than walking into class without a clue and using this precious time with a teacher to write everything down.

Tip 7. Create your study materials

Once you’ve read the textbook and been to the lecture, it’s a great time to make flashcards. Doing this now (rather than waiting until right before the exam) will consolidate the knowledge and make it easier for you to study later.

In essence, you’re front-loading your study time. As any good gardener knows, the seeds you sow now will bear fruit later. Spend a little more time now putting information into your long-term memory, and when it comes time to revise for your test, you’ll be way ahead.

We’re not at all biased (or maybe we are) but know that Brainscape is the best damn flashcard tool out there for serious learners. Science says so. The Brainscape algorithm paces your learning so you absorb new knowledge twice as fast. This is done via spaced repetition: introducing new information at the right rate for your brain to absorb it, and revisiting it at the perfect time for your brain to store it in long term memory.

Active recall and spaced repetition help you become a learning machine, and with our online flashcards app, you can study anywhere, taking advantage of small pockets of time to master your subjects.

Make active reading a habit

Now you know how to read a textbook and actually remember what you learned.

The final step to becoming a learning ninja is to make all this a habit, and incorporate active reading and Brainscape flashcards into your overall study habits . This might feel like a fair amount of upfront work, but once it’s an automatic and non-negotiable part of your studies, you’ll end up spending less total time studying.

You’ll become one of those annoying students who have plenty of time to do fun stuff during study week, and still walk away with top grades. Just as importantly, knowing how to engage in active reading will turn you into an effective-life long learner.

At Brainscape, we believe being able to master hard subjects is a skill that compounds over time, and will put you on a career trajectory that leads to exciting places.

Sources

Allen, M., LeFebvre, L., LeFebvre, L., and Bourhis, J. (2020). Is the pencil mightier than the keyboard? A meta-analysis comparing the method of notetaking outcomes. Southern Communication Journal 85(3), 143-154. https://doi.org/10.1080/1041794X.2020.1764613

Cohen, P. A., Kulik, J. A., and Kulik, C. L. C. (1982). Educational outcomes of tutoring: A meta-analysis of findings. American Educational Research Journal, 19(2), 237-248. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00028312019002237

Küçükoğlu, H. (2013). Improving reading skills through effective reading strategies. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 709-714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.113

- Optimize your brain health for effective studying

- How to build strong study habits

- How to study effectively: The ultimate guide

- Finding study motivation when you want to procrastinate

- ‘I can’t concentrate!’ How to focus better when studying

- Interleaving practice makes perfect: “mix it up” to learn faster

- How to study for the AP exams more efficiently

- How we learn: the secret to all learning and human development

- The secret to learning more while studying less: adaptive learning

- Do snoozers really lose? Can naps boost creativity and memory?

- Your ticket to medical Spanish fluency just arrived!

- How to apply for FAFSA student aid

- How to level up your personal growth with Brainscape

- Brainscape’s early childhood app gives kids a powerful head start

- Do flashcards help kids with dyslexia?

- Teachers