Physical Address

Of course, it’s best to know all of these.

Anki: Advice, Tips and Resources for Spaced Repetition

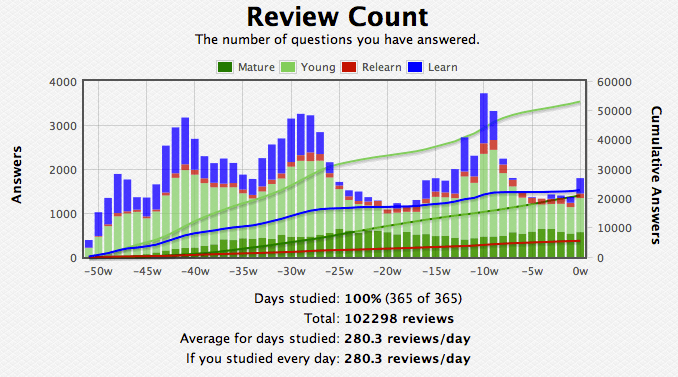

I’ve been using Anki for language studying (especially for Japanese) daily for 2 years.

I’ve had mixed results using custom decks for concepts I learned in university, where I found anki really helped me memorize things but I generally didn’t have a lot I needed memorizing in the first place (I wonder which subjects present a memory bottleneck instead of a, for instance, understanding bottleneck).

Where Anki has really shone for me is vocabulary acquisition in Japanese. I studied Japanese using the DJT method, where I first memorized a big deck of vocabulary cards (mostly N3 words, for those who care), and then started reading a Light Novel daily (in my case, Kumo Desuga Nanika) and “mining” for new words: every time I found a word I didn’t know, I would add a card to my vocab deck with the sentence where I first found it (sometimes edited for brevity, leaving out superfluous words). I do daily reading sessions of one hour, and daily anki reviews, and after one year of this I can safely say I went from lower-N3 (JLPT3) level to a place where I can confortably read a light novel or watch anime without subs (my current average is two unknown words every 3 light novel pages read). I am currently at ~2k mined words, and my reviews take about 15 minutes/day (though I also do writing exercises in between, because I like calligraphy).

What follow are quotes and opinions on using Spaced Repetition for studying, collected from diverse sources: Michael Nielsen’s essay, Gwern’s amazing essay, and a few others. Feel free to contact me if you think of a different resource, quote or tip that could fit here! I will probably keep updating this post if I come up with anything worthwhile.

Helping Develop Virtuoso Skills with Personal Memory Systems, Michael Nielsen

“As we’ll see, Anki can be used to remember almost anything. That is, Anki makes memory a choice, rather than a haphazard event, to be left to chance. I’ll discuss how to use Anki to understand research papers, books, and much else. And I’ll describe numerous patterns and anti-patterns for Anki use. While Anki is an extremely simple program, it’s possible to develop virtuoso skill using Anki, a skill aimed at understanding complex material in depth, not just memorizing simple facts.

I therefore have two rules of thumb. First, if memorizing a fact seems worth 10 minutes of my time in the future, then I do it. Second, and superseding the first, if a fact seems striking then into Anki it goes, regardless of whether it seems worth 10 minutes of my future time or not. The reason for the exception is that many of the most important things we know are things we’re not sure are going to be important, but which our intuitions tell us matter. This doesn’t mean we should memorize everything. But it’s worth cultivating taste in what to memorize.

What can Anki be used for? I use Anki in all parts of my life. Professionally, I use it to learn from papers and books; to learn from talks and conferences; to help recall interesting things learned in conversation; and to remember key observations made while doing my everyday work. Personally, I use it to remember all kinds of facts relevant to my family and social life; about my city and travel; and about my hobbies. Later in the essay I describe some useful patterns of Anki use, and anti-patterns to avoid.”

His steps for making Anki cards on a paper (I guess they apply to book chapters too):

- First pass: add basic questions easily picked up from looking at the text (What is the win condition in this game?).

- Second pass: add conceptual or more complicated questions, which require a certain understanding of the text.

- Third pass: High level questions that require a deep understanding of the subject.

Note: for a single paper, Nielsen makes tens, sometimes “several hundred” cards.

Tips for Card Making

Make most Anki questions and answers as atomic as possible One benefit of using Anki in this way is that you begin to habitually break things down into atomic questions. This sharply crystallizes the distinct things you’ve learned. In general, I find that you often get substantial benefit from breaking Anki questions down to be more atomic. It’s a powerful pattern for question refactoring.

Note that this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t also retain some version of the original question.

Anki use is best thought of as a virtuoso skill, to be developed

Anki isn’t just a tool for memorizing simple facts. It’s a tool for understanding almost anything.

Avoid orphan questions. Avoid the yes/no pattern

Cultivate strategies for elaborative encoding / forming rich associations. This is really a meta-strategy, i.e., a strategy for forming strategies. One simple example strategy is to use multiple variants of the “same” question.

Procedural versus declarative memory: There’s a big difference between remembering a fact and mastering a process.

“By analogy with code smells, we can speak of “question smells”, as suggesting a possible need for refactoring. A yes/no construction is an example of a question smell.”

Ebbinghaus found that the probability of correctly recalling an item declined (roughly) exponentially with time. Today, this is called the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve.

Spaced Repetition, Gwern

The research favors questions which force the user to use their memory as much as possible; in descending order of preference:

- free recall

- short answers

- multiple-choice

- Cloze deletion

- recognition

the research literature is comprehensive and most questions have been answered – somewhere.

the most common mistakes with spaced repetition are

- formulating poor questions and answers

- assuming it will help you learn, as opposed to maintain and preserve what one already learned. (It’s hard to learn from cards, but if you have learned something, it’s much easier to then devise a set of flashcards that will test your weak points.)”

“OK, but what does one do with it? … Now that I have all this power – a mechanical golem that will never forget and never let me forget whatever I chose to – what do I choose to remember?”

“Multiple choice tests can accidentally lead to ‘negative suggestion effects’ where having previously seen a falsehood as an item on the test makes one more likely to believe it.

This is mitigated or eliminated when there’s quick feedback about the right answer. Solution: don’t use multiple choice; inferior in testing ability to free recall or short answers, anyway.”

What To Add

“I find one of the best uses for Mnemosyne is, besides the classic use of memorizing academic material such as geography or the periodic table or foreign vocabulary or Bible/Koran verses or the avalanche of medical school facts, to add in words from A Word A Day and Wiktionary, memorable quotes I see, personal information such as birthdays (or license plates, a problem for me before), and so on. Quotidian uses, but all valuable to me. With a diversity of flashcards, I find my daily review interesting. I get all sorts of questions – now I’m trying to see whether a Haskell fragment is syntactically correct, now I’m pronouncing Korean hangul and listening to the answer, now I’m trying to find the Ukraine on a map, now I’m enjoying some A.E. Housman poetry, followed by a few quotes from LessWrong quote threads, and so on. Other people use it for many other things; one application that impresses me for its simple utility is memorizing names and faces of students although learning musical notes is also not bad.

It’s interesting to compare SRS decks to the feat of memorizing Paradise Lost or to the Muslim title of ‘hafiz’, one who has memorized the ~80,000 words of the Koran, or the stricter ‘hafid’, one who had memorized the Koran and 100,000 hadiths as well.”

From rs.io

Tips for Cardmaking and Anki Use

- Why questions: Cards that answer the question “Why?” are more valuable than factual cards. My emerging perspective here is that it’s important to understand all the context of an idea to really know it. How it emerged, how to invent it, what it’s for, and so on.

(this ties nicely to what Nielsen says too. Add a question and its reverse, add different wh questions, split a concept into atomic bits.)

- Connections: “The biggest problem with Anki is the tendency for cards to become disconnected” (…) “I now construct more cards that enforce links between knowledge. I might ask, “How is this concept different from that concept?”

(I like this idea: add cards about each concept, but also about relationships between them. This way you can kill more birds with a single stone.)

- Two-way connections: Don’t just add cards like “what’s X?”, “What’s the name of the Y that Z?”. Also add things like “What’s the name of something or other?” (it is X) and “what is W?” (it’s the Y that Z). Basically, a card’s question should be a reverse card’s answer, and viceversa.

“Has your computer ever spat out an error message and, although you remember seeing it before, you don’t remember how to fix it? Before I started Janki Method this would happen to me a lot.

The first time I saw the issue I would spend half a day solving the problem. Six months later the problem would happen again, perhaps in a slightly different form. Even though I was vaguely aware of having seen it before, I’d forgotten how to fix it.

After solving a bug you should always add some cards to your deck containing the knowledge needed to prevent that bug from occurring again. Better yet, abstract one level and add cards containing the knowledge needed to prevent that class of bugs. Now, whenever you are faced with a bug the second time, all you need to do is search your archives.” – Jack Kinsella

“If I look something up in StackOverflow, I’ll add it to Anki. Wikipedia? Another Anki card.”

“If you have time, think about where you learned the card”

Syntax for cloze deletion is \\>

Anki Tips: What I Learned Making 10,000 Flashcards

If you don’t know what Anki or spaced repetition is, start by reading gwern’s excellent introduction.

This month, I created my ten thousandth virtual flashcard. When I started using Anki, I worried that I’d do the wrong thing, but decided that the only way to acquire Anki expertise was to make a lot of mistakes.

Here’s how my Anki usage has evolved.

Why questions

Cards that answer the question “Why?” are more valuable than factual cards. (See also this post.) It’s easy to memorize that QuickSort has a lower bound of O(n lg n), but better to know why it has such a lower bound, and even better still to understand why comparison-based sorts can’t be faster than O(n lg n).

Of course, it’s best to know all of these.

My emerging perspective here is that it’s important to understand all the context of an idea to really know it. How it emerged, how to invent it, what it’s for, and so on.

Images

My original Anki decks were all words. Now, I lean on images as heavily as possible. I find, at least for my sort of mind, that most of understanding something is learning to visualize and manipulate it mentally. Google image search is one of my first stops. In a pinch, I also make crude drawings of my own. As long as it captures the main idea, it’ll do:

As an unintended consequence, my thought itself has shifted towards more imagery. The repetition makes an image representation of a concept more available mentally than its equivalent in words.

Connections

The biggest problem with Anki is the tendency for cards to become disconnected, so that a lot of knowledge is only available with the right cue and, even then, it’s a sort of impoverished thing.

I’m not aware of any silver bullet for this problem, but I now construct more cards that enforce links between knowledge. I might ask, “How is this concept different from that concept?” Or how a concept explains something from my personal life, or what an idea is reminiscent of.

The main limitation here is the general unavailability of a piece of information. With the right cue, I can recall it, but it’s not as if I can just sit down and brain dump every single one of my memories.

Mnemonics, at least the method of loci, are a bit better in this regard, as I can think myself to a place if I need to retrieve something.

Single deck

Currently, I have decks organized by topic and subtopic. However, I now think this is backwards. Given Hebbian learning — neurons that fire together wire together — I’m convinced that mixing everything is superior.

Take the production of insight, for instance. I find that insight often arises when two ideas that have been recently activated in memory collide and I think, “Oh, wait, that’s related to that.”

If everything is carefully partitioned, you limit opportunities for this serendipity. Topic organization says “ideas about computer science don’t belong with those about economics,” except applying ideas across disciplines is precisely where the insights are likely to be most fertile.

Two-way connections

Here’s a mistake I’ve made a couple of times. You’ll be reading a text and it’ll define something, like the Martin-Löf-Chaitin thesis, and you’ll create a card saying, “What’s the Martin-Löf-Chaitin thesis?”

Then, sometime in your life, you’ll be sitting and thinking, “Hey, what’s that mathematical theory of randomness called?” and you won’t know, because you didn’t make a card like that, and your mind only learned the connection one way.

This has also happened with cuckoo hashing and I’m sure other things too, so now I make more of an effort to learn something forwards and backwards, like “What’s cuckoo hashing?” and “What’s the name of that probabilistic version of hashing?”

In general, poor models of how memory and mind work hinder Anki effectiveness. You might think, hey, knowing something is all there is to knowing. Wrong. A lot of knowing is creating different cues and representations of that knowledge so that you can recall it when needed.

A great deal of an effective knowledge base is engineering it so that it’ll be useful in the sort of situations where you expect to apply it.

Adding whatever

My philosophy when I started using Anki was to add whatever, to just adopt a trifling barrier to entry. I didn’t worry about whether a fact is useful or not or anything like that. If something appealed to me, I’d add it.

This core is remains. The main change this philosophy has undergone is to shift away from setting a specific study time and making cards during that study time. Instead, I add anything interesting, regardless of when it happens, and random connections and insight that occur to me throughout the day.

For example, each morning I go through my RSS reader and check the news for the day. Whenever I come across something interesting or insightful, I add it.

Or here’s a common hangup people have, and that I had, when starting with spaced repetition. It’s the question, “What ought I memorize?” and people think, well, maybe the presidents or something, because that’s what they’ve associated memorization with.

It’s the wrong question. Ask “What’s interesting?” and start ankifying that.

People also really like it when you can recall minutia about them, too, which is sort of fun. If someone mentions their favorite type of cheese, or a pet’s name, make it into an Anki card. It’s like free social points. Memorizing birthdays works.

Thoughts on the value of Anki

I remain, more than a year later, enthusiastic about Anki. The honeymoon period is over and I still think it’s awesome.

Anki-powered studying has become my new normal. Whenever I regress to trying to memorize something spontaneously, without software assistance, like command line flags or some bit of HTML, it’s frustrating. It feels like something is wrong, like it ought to be so much easier, because with Anki it is.

Which is not to say that Anki is a panacea. Just as it’s a good idea to diversify your stock portfolio, it’s a good idea to diversify learning methods.

Further Reading

- I’ve written before about the importance of “Why?” questions, on structuring knowledge, and on different modes of thinking about mathematics (but which are broadly applicable).

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.